Paleontology News

How early sharks with odd jaws ate their prey

Paleontologists show how early sharks could swing their jaws outward to capture prey

Summary Points

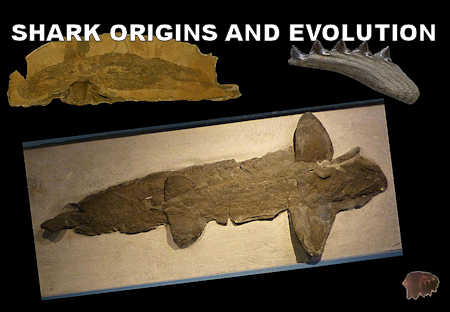

Fig. 4 from Frey et al., 2020 showing the composite model of the new sharks jaws.

Early sharks did not rapidly replace their teeth like modern sharks and their larger and sharper teeth pointed inward toward their mouths.

Using CT scans and a 3D printed model, paleontologists determined that early sharks could rotate their jaws outward, revealing the larger teeth when feeding.

This type of jaw mechanics became obsolete over time as tooth replacement became increasingly faster. Eventually this type of jaw was replaced by the jaws that modern-day sharks have.

The findings were based on a well preserved specimen of a new Devonian shark from Morocco called Ferromirum oukherbouchi.

3D model shows how early sharks could swing their jaws outward to capture prey

This article is based on a Press Release by the University of Zurich - November 18, 2020, and the Journal Article (Frey et al, 2020)

Figure 4 from Frey et al., 2020 showing an image, line drawing, and zoomed in portions of the new shark specimen.

Early sharks of the Paleozoic were much different than modern sharks. One major difference is the teeth and jaws. Modern sharks rapidly replace their teeth and have the sharp new ones pointing outward from the jaws. Early sharks did not replace their teeth nearly as much and the new teeth pointed inward toward their mouths.

Paleontologists have wondered how these early sharks could grasp onto their prey, since the sharp teeth pointed the wrong way. Recently, paleontologists at the University of Zurich, the University of Chicago and the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden (Netherlands) solved this mystery. They examined a new and well-preserved Devonian shark that shows how its jaw mechanics worked.

They reconstructed the jaws of a 370 million year old shark from Morocco called Ferromirum oukherbouchi . They used computed tomography scans and was able to print out a 3D model of the jaws.

What they discovered was the jaws were not fused in the middle, which allowed the shark to open its mouth and also rotate the jaws outward, revealing the younger, larger, and sharper teeth. These teeth could then easily impale their prey. As the jaws closed, the teeth would then rotate back inwards, pushing the prey deeper into the jaws.

The researchers also conclude the unique rotating jaws not only enabled the larger inward facing teeth to be used, but also allowed the animal to preform suction-feeding. As Christian Klung says, "In combination with the outward movement, the opening of the jaws causes sea water to rush into the oral cavity, while closing them results in a mechanical pull that entraps and immobilizes the prey."

Christian Klung also said this type of jaw played an important role in Paleozoic sharks, however, as tooth replacement became increasingly faster, this type of jaw became obsolete and was replaced by the jaws that modern-day sharks have.

Journal Article:

Frey, L., Coates, M.I., Tietjen, K. et al. A symmoriiform from the Late Devonian of Morocco demonstrates a derived jaw function in ancient chondrichthyans. Commun Biol 3, 681 (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s42003-020-01394-2

Recommended Shark Book:

Sharks of the World (Princeton Field Guides)

Leonard Compagno, Marc Dando, and Sarah Fowler (2005)

This book is written by THE WORLDS LEADING shark experts!

Chalk full of illustrations and maps, its a field guide to all the 440+ shark species out there.

The book also has chapters on shark physiology and behavior. It's a must for any shark lover! There are usually cheap paperback copies available, check it out!