Article written by: Jayson Kowinsky - Fossilguy.com

Gomphotherium: "Welded Beast"

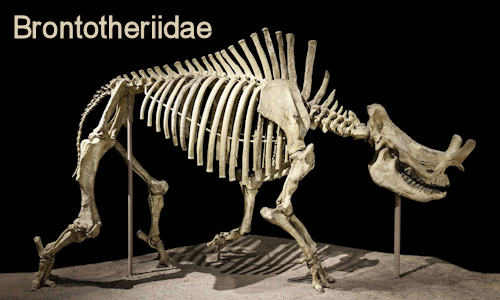

A Gomphotherium specimen on display at the Palaontologisches Museum in Munchen. Image by Szilas.

Gomphotherium - Facts about the prehistoric elephant

Fast Facts

Illustration of a Gomphotherium angustidens by Nobu Tamura. CC BY-SA

Name:

Gomphotherium (pronunciation: "Gom-Foe-Thirion")

The name means "Welded Beast" - named after the long straight tusks of the lower jaw.

Taxonomy:

Mammalia (Mammal Class) - Proboscidea (Order) - Gomphotheriidae (Family) - Gomphotherium (Genus)

Generally accepted species:

Gomphotheres were very successful. As a result, there were many species; some of which need revised.

North American species include G. productum, G. calvertensis, G. cimarronis, G. simplicidens and G. hondurensis.

Age: Early Miocene to Early Pliocene.

Extinction: Early Pliocene

However, close relatives in the Gomptheriidae family survived until the Pleistocene Ice Ages.

Distribution: Nearly Global

Nearly Global: Africa, Europe, Asia, North and Central America.

Close relatives in the family also spread into South America.

Body Size:

Most species were around the size of an Asian Elephant. G. steinheimense was a bit larger.

Description:

Gomphotheres had 4 tusks; two enamel coated tusks in the upper jaw and 2 tusks in the lower jaw.

Their teeth had very high ridges and they had an elongated skull with a short tail and were covered by hair

Ecology/Diet: Herbivore:

They lived in Woodland and Shrubland environments eating branches.

Fun Facts:

They were an incredibly successful group of elephants. One species is part of the evolutionary line that gave rise to modern elephants.

Introduction / Physical Description

This illustration shows the sizes of two Gomphotherium specimens, G. productum and G. steinheimense. From Appendix 1 of Larramendi (2016).

Gomphotheres were early elephants that looked different from modern elephants. Gomphotheres had 4 tusks; 2 straight ones in the upper jaw and 2 straight ones in the lower jaw. Unlike elephants today, the upper tusks were coated with enamel. Gomphothere teeth had very high ridges, which were ideal for grinding very tough foods, like branches. The skull of Gomphotheres were also elongated and they had shorter legs and a more barrel shaped body than modern elephants. Research by Larramendi (2016) looked at the tail vertebra of various species and found that most Gomphotheres had very short tails. Although they are often depicted without much hair, Larramendi (2016) suggests Gomphotheres were covered in hair. Finally, Larramendi (2016) comments that elephant trunks must be long enough to reach the ground without bending of the knees. Therefore, gomphotheres probably had normal length trunks. Most Gomphotheres were similar in size to the Asian Elephant, however G. steinheimense was larger.

A cast of the skull and mandibles of Gomphotherium productum (Specimen PV M 50540) from the British National History Museum Online British Museum Collections. CC0-1.0

Two views of an upper left M3 Molar of Gomphotherium libycum (Specimen PV M 21866) from the British National History Museum Online British Museum Collections. CC0-1.0 . Specimen collected from the Miocene of Lybia.

Origins, Distribution, and Species

Gomphotheres were a very successful type of early elephant. They are attributed to a second elephant radiation event, where elephants migrated out of Africa and spread into Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Although they are extinct, the species G. steinheimense is part of the evolutionary line that gave rise to modern elephants (Wu Y. et al., 2018).

Origin and Distribution

Gomphothere like animals first appear on the fossil record in the late Oligocene of Eastern Africa.

A notable example is Eritreum melakeghebrekristosi from Eritrea, which is near Ethiopia (Shoshani, 2006).

By the early Miocene, Gomphotheres have a fossil record in Africa,

Europe, Asia, and even into Japan (Miyata and Tomida, 2010).

Sometime by the Middle Miocene, Gomphotheres spread into North America,

and by the Late Miocene into the Pliocene they are also found in Central America.

The southernmost occurrence of the genus Gomphothere is from Panama (MacFadden, et al., 2015).

Close relatives in the Gomphotheriidae family even spread into South America during the Pliocene and Pleistocene.

Species

Like many other fossil taxa, the Gomphothere taxon is very messy and probably needs revised.

Currently, there may be up to 20 accepted species. However, many of the species are based on isolated material.

To help simplify things, the Gomphotherium taxon is often divided into 4 evolutionary groups with a range of species in each group.

Below is a list of the groups and species provided by Wang, et al. (2017).

Wang et al. (2017) gives four taxonomic groups:

1.The Old World Group: This is an ancestrial group which is often called the annectens group.

It contains earlier species from Africa, Europe, and Asia, including G. annectens, G. sylvaticum, and G. cooperi.

2. The African Taxa: This group is a separate evolutionary line that is unique to Africa.

It includes G. libycum and G. pygmaeus.

3. The Angustidens Group: This is another separate evolutionary group in Europe and Asia.

It includes G. inopinatum, G. mongoliense, G. connexum, G. angustidens. The Chinese species G. shensiensis, and G. connexum.

4. The Derived Gomphotherium Group: Contains later gomphotheres from the middle to late Miocene in Europe, Asia, and also North America.

It includes G. subtapiroideum, G. tassyi, G. wimani, G. browni, and G. steinheimense.

North and Central American species are also included in the Derived Group.

American Gomphothere species include G. productum from the Midwest,

G. calvertensis from the Calvert Cliffs of Maryland and Virginia, G. cimarronis from Texas,

G. simplicidens from Florida, and G. hondurensis from Central America.

Ecology and Diet – Woodland Browsers

A 1901 painting by Charles R. Knight that shows a Gomphothere eating vegetation from a tree. Public Domain.

Gomphotheres have molars with very high ridges making them efficient for grinding tough vegetation such as tree limbs and bark.

Most gomphotheres probably lived in wooded environments while using their tusks to shear vegetation from trees and shrubs.

A common misconception is that Gomphotheres lived in swampy environments and used their shovel like lower tusks to scoop vegetation from lakes. However, this is clearly not the case.

Fox and Fisher (2004) studied the C-3 vs C-4 ratios in tusks to reconstruct the dietary habits of Gomphotheres in North America

and found they stayed in wooded habitats and ate from trees and shrubs. Similar results were found in China by Zhang et al. (2016).

Also, separate studies have looked at wear marks on both upper and lower tusks to determine how they used them.

An extreme example is Platybelodon. Platybelodon is a genus in the Gomphothere family that had very flat and

wide lower tusks that were actually shaped like a shovel. Lambert (1992) studied the wear tusk patterns of this

genera and similar ones to concluded they used both their upper and lower tusks to shear off bark and vegetation from trees.

They did not scoop vegetation from lakes.

A life-sized model head of a Gomphothere on display at the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles.

Extinction – The Expansion of Grasslands

Gomphotheres were an earlier group of elephants that were well suited for eating hard materials,

such as tree branches and shrubs. As the Miocene was coming to an end, the global climate changed becoming

cooler and more arid (Chaimberlan et al., 2014). This caused global ecosystems to change from forested environments

to grasslands, which in turn influenced mammal evolution (Cerling et al., 1993 and Janice, 1993).

Although the climate and ecosystems were changing, the diets of Gomphothereium remained more or less the same.

Research shows they continued to mainly eat from wooded environments in North America (Fox and Fisher) and

also in China (Zhang, Want et al 2016).

So, while specialized grazing mammals were spreading and flourishing at this time, Gomphotheres were dwindling.

By the middle Pliocene, traditional Gomphothere habitats had vanished and Gomphotheres went extinct. They were

replaced with more modern elephants that had flatter ridges on their molars that enabled them to grind grasses better.

These new elephants that took over the new ecological niches were the modern African Forest and African Savannah elephants.

Although the Gomphothere genus became extinct in the Pliocene, a few members of the Gomphotheriidae family survived until the Holocene Ice Ages.

Examples include the genus Cuvieronius and Notiomastodon (Stegomastodon) which migrated into South America (Prado and Alberdi, 2008). These animals

specialized and adapted to the cooler climate and ecological changes. They had lost the enamel on their upper tusks,

lost or severely reduced their lower tusks (Mothe et al., 2016) and had mixed browsing but also grazing diets (Pérez-Crespo et al., 2016).

These genera went extinct rather recently in the Holocene, during the Ice Ages 12,000 to 10,000 years ago.

In fact, a Notiomastodon from Brazil was found with an artifact embedded in it, indicating it was hunted by humans (Mothe et al., 2020).

Works Cited:

Cerling, T., Y. Wang, and J. Quade (1993). Expansion of C4 ecosystems as an indicator of global ecological change in the late Miocene, Nature, 361, 344–345.

Chamberlain, C., Winnick, M., Hari, M., Chamberlain, S., Katharine M. (2014). The impact of Neogene grassland expansion and aridification on the isotopic composition of continental precipitation. Global Biogeochemical Cycles. DOI: 10.1002/2014GB004822..

Fox, D., and Fisher, D. (2004). Dietary reconstruction of Miocene Gomphotherium (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the Great Plains region, USA, based on the carbon isotope composition of tusk and molar enamel. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 206. 311-335. 10.1016/j.palaeo.2004.01.010.

Janis, C. M. (1993). Mammal evolution in the context of changing climates, vegetation and tectonic events, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst., 24, 467–500.

Lambert, W. (1992). The feeding habits of the shovel-tusked gomphotheres: evidence from tusk wear patterns. Paleobiology. 18.

Larramendi, A. (2015). Shoulder Height, Body Mass and Shape of Proboscideans. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 61. dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.00136.2014.

Lucas, S. and Morgan, G. (2005). ICE AGE PROBOSCIDEANS OF NEW MEXICO. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 28. 255-261.

MacFadden, B., Morgan, G., Jones, D., and Rincon, A. (2015). Gomphothere proboscidean (Gomphotherium) from the late Neogene of Panama. Journal of Paleontology, 89(2), 360-365. doi:10.1017/jpa.2014.31 DOI:10.1017/jpa.2014.31.

Mothe, D., Ferretti, M. P., and Avilla, L. S. (2016). The Dance of Tusks: Rediscovery of Lower Incisors in the Pan-American Proboscidean Cuvieronius hyodon Revises Incisor Evolution in Elephantimorpha. PloS one, 11(1), e0147009. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0147009.

Mothe, Dimila & dos Santos Avilla, Leonardo & Araújo Júnior, Hermínio & Rotti, A. & Prous, A. & Azevedo, S.A.K.. (2020). An artifact embedded in an extinct proboscidean sheds new light on human-megafaunal interactions in the Quaternary of South America. Quaternary Science Reviews. 229. 106125. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.106125.

Prado, J.L. and Alberdi, M.T. (2008), A CLADISTIC ANALYSIS AMONG TRILOPHODONT GOMPHOTHERES (MAMMALIA, PROBOSCIDEA) WITH SPECIAL ATTENTION TO THE SOUTH AMERICAN GENERA. Palaeontology, 51: 903-915. DOI:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00785.x.

Shoshani, J., Walter, R. C., Abraha, M., Berhe, S., Tassy, P., Sanders, W. J., Marchant, G. H., Libsekal, Y., Ghirmai, T., and Zinner, D. (2006). A proboscidean from the late Oligocene of Eritrea, a "missing link" between early Elephantiformes and Elephantimorpha, and biogeographic implications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103(46), 17296–17301. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0603689103.

Pérez-Crespo, V. A., Prado, J. L., Alberdi, M. T., Arroyo-Cabrales, J., Johnson, E. (2016). Diet and Habitat for Six American Pleistocene Proboscidean Species Using Carbon and Oxygen Stable Isotopes. Ameghiniana, 53(1), 39-51.

DOI:10.5710/AMGH.02.06.2015.2842.

Miyata, K. and Tomida, Y. (2010). Anchitherium (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Equidae) from the early Miocene Hiramaki Formation, Gifu Prefecture, Japan, and its implication for the early diversification of Asian Anchitherium. Journal of Paleontology. 84. 763-773. DOI:10.1017/S0022336000058479.

Wang, Shiqi & Li, Yu & Duangkrayom, Jaroon and Yang, Xiang-Wen & He, Wen & Chen, Shan-Qin. (2017). A new species of Gomphotherium (Proboscidea, Mammalia) from China and the evolution of Gomphotherium in Eurasia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. e1318284. DOI:10.1080/02724634.2017.1318284.

Yan Wu, Tao Deng, Yaowu Hu, Jiao Ma, Xinying Zhou, Limi Mao, Hanwen Zhang, Jie Ye, and Shi-Qi Wang. (2018). A grazing Gomphotherium in Middle Miocene Central Asia, 10 million years prior to the origin of the Elephantidae. Scientific Reports, 8(1) DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-25909-4.

Recommended Prehistoric Mammal Books:

Additional Images of Gomphotherium:

Gomphotherium calvertnsis tooth from the Calvert Cliffs of Maryland. Specimen from the National Museum of Natural History - Smithsonian Online Collections. CC0

Other Prehistoric Beasts of the Cenozoic!

About the Author

Contact Us

To ask Questions about Paleontology, Fossil Identification, Image Use, or anything else, email us.

Fossilguy.com is very active on Facebook, you can also message us there!

We don't buy or sell fossils, so please don't email us asking about the value of a fossil or fossil purchases.

Visit us on Social Media:

Enjoy this website?

Consider a Paypal / Credit Card donation of any size to help with site maintenance and web hosting fees:

Privacy Policy and Legal Disclaimer

Back to the TOP of page

REWILD - Resotring Nature one Native Plant at a Time

© 2000 - 2025 : All rights reserved

Fossilguy.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising

fees by advertising and linking to amazon.com