Shark Origins and Evolution

The Cladoselache genera - One of the best known sharks from the Celveland Shale.

Prehistoric Sharks: Shark History and Evolution Through Time

Sharks are fish of the condrichthyes class. The condrichthyes are a truly ancient class of fish, and are the ultimate survivors.

Their fossil record predates most animals,

including all land animals (dinosaurs included), trees, and even insects!

They have survived all 5 major mass extinctions, including the Permian one that wiped out most life on Earth.

Since sharks are made of cartilage, they do not preserve very well. Usually only their dermal denticles

(modified scales) and teeth readily fossilize. Because of this, their origins are fragmentary,

yet we still have a good idea of when they first appeared.

The First Sharks - Ordovician Beginnings - 450 Mya

The first sharks come to us from the Ordovician radiation event around 450 Million years ago. The Ordovician radiation, or more impressively called the

"Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event," arguably rivals the more famous Cambrian Explosion of the previous time period.

During this biodiversification event, Earth experienced an unprecedented explosion of new classes, orders, families, genera,

and species, including the chondrichthyes. It was evolution on steroids.

The first shark-like fossils found are dermal denticles (skin scales), discovered in the Harding Sandstone of Colorado (Samson et al 1996)

and in the Carmichael Sandstone of the Stokes Formation in Australia (Young 1997).

Later, the dentine that forms shark denticles found in the Harding Sandstone was found on the fin scales of the small

spotted catshark (Zerina 2008). As a result it was concluded the world's oldest sharks were in the Harding and Carmichael Sandstone.

In 2016, Andreev et al. reviewed Ordovician dermal denticles, including ones from the Harding Sandstone,

and also concluded they are condrichthyes and named them Solinalepis gen. nov.

In 2012, Sansom et al. described more shark-like scales from the

Stairway Sandstone in central Australia, which is middle Ordovician.

He named these ones Tantalepis gatehousei (Sansom et al 2012), which is now officially the world's oldest named shark.

An interesting thing to note is only dermal denticles, and not teeth, have been found. Jawed fish were just developing at this time,

so the first sharks may have had no teeth or maybe even no jaws! It appears teeth developed later. So, according to the fossil

evidence, a shark tooth is simply a modified denticle; albeit a great big and sharp modified denticle!

This figure shows two shark-like denticles from the Harding Sandstone of Colorado. The age is roughly 455 million years old. These are possibly the worlds oldest shark fossils.

These denticles, like modern shark denticles, have raised areas, or crowns, running across the surface. The center crown is the largest.

The image was taken from a standard microscope (hence, the elevated regions are out of focus).

The scales are about 0.4 mm across.

The Silurian - A Scant Shark Record - 443 Mya

Except for a possible fin spine (sinacanthus wuchanthus), the Silurian fossil record starting at 443 Million years ago continues

to be represented only by isolated shark denticles.

Silurian dentilces were originally found in the Upper Silurian Pitchi-Shui Formation in Tuva (Southern Siberia).

They were described by Karatajute & Talimaa (1973) and are given the genus name elegestolepis.

Since then, allot of work has been done in the Silurian of Monglolia and these primitive Silurian Chondrichthyes

have been placed in the Mongolepidida order (Karatajute-Talimaa et al. 1990).

In the mid 1990's and 2000's many more chondrichthian denticles have been discovered in throughout Asia and even Canada.

Genera now include elegestolepis, mongolepis, teslepis, sodolepis, shiqianolepis, and pilolepis (Andreeev et al. 2016).

Some of these, including the possible fin spine, are shown in the image below.

This figure shows a sample of Silurian chondrichthyan (shark) fossils. (A) Mongolepis rozmanae (B) Xinjiangichthys pluridentatus (C) Shiqianolepis hollandi

(D) Elegestolepis grossi (E) Pilolepis margaritifera (F) Sinacanthus wuchangensis.

From Qu et al, 2010. Image from researchgate.net Accessed 23 Dec, 2017

The Devonian Radiation of Sharks - 419 Mya

Doliodus problematicus (NBMG 10127), from the Lower Devonian of New Brunswick, Canada. This is the oldest intact shark fossil. Image from:Maisey et al, 2017

The Devonian period (starting around 419 million years ago) not only saw the worlds first tetrapods appear,

it also saw a great radiation of all fish including sharks. This is why the Devonian period is called the "Age of Fishes."

It is not until the Age of Fishes that fossil shark teeth and complete shark fossils appear.

The world's oldest intact shark fossil is of a specimen called Doliodus problematicus (NBMG 10127) - shown above.

It is Lower Devonian (around 400 million years old) and comes from the Campbellton Formation in New Brunswick, Canada (Miller et al 2003).

This specimen shows shark characteristics mixed with characteristics of acanthodians, a primitive class of fish (Maisey et al 2017).

The best-preserved specimens of complete fossilized Devonian sharks are from the Late Devonian Cleveland Shale.

The shark fossils of the Cleveland Shale near Lake Erie in Ohio are so well preserved that muscle fibers are

preserved and even remains of prey in the gut can be studied (Hansen, M.C. 1996, p. 290). The Cleveland Shale

contains a variety of shark specimens. There are several species of the streamlined genera Cladoselache

(sketched in the introduction image), as well as other genera such as Diademodus, Stethacanthus, Ctenacanthus,

and Orodus (Hansen, M.C. 1996, p. 290). These Devonian sharks looked very different than extant sharks.

They were smaller, were shaped differently, and some even lived in fresh water. To the untrained eye, they

looked more like fish than sharks. Below are some fossil examples from the Devonian.

Large Cladoselache shark fossil from the Cleveland Shale. This specimen is on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History

This image shows the late Devonian fossil shark tooth, Ageleodus pectinatus.

This specimen measures ~4 mm across. It is from the famous Red Hill locality in Pennsylvania,

and is approximately 364 million years old.

This is the earliest occurrence of Ageleodus.

The tooth has a series of cusps forming a comb like structure with a porous root.

These Ageleodus teeth are found in fresh water river deposits, meaning it was a freshwater shark, which was not uncommon in the Paleozoic.

Carboniferous - The Golden Age of Sharks - 359 Mya

This is a casting of a helicoprion dental spiral at the aquarium of the Porte Doree in Paris during a temporary exhibition on sharks. Image Credit: Thesupermat - Own work CC BY-SA 3.0

The Devonian time period ended with a major mass extinction around 374 million years ago. One of the many casualties of this mass extinction was the Placoderms (armored fish). Armored fish were the prevailing class of fish; Placoderms included the Devonians top predator, the 20 foot long Dunkleosteus. The extinction of this top class of predators left a large ecological hole. Immediately afterward, in the Carboniferous period, sharks seized the opportunity and became the top predators. The Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian and Mississippian epochs) marks the high watermark of sharks. Although the Carboniferous is known for it's huge coal forests and the radiation of amphibians, it is also known as the "Golden Age of Sharks."

Excellent preserved specimens from this Golden Age come from limestone beds in the Heath Shale Formation which is of the Mississippian Epoch (318 million years old) (Lund & Grogan 2005). A famous limestone bed in this formation is called the Bear Gulch Limestone found in Fergus County, Montana. This lagerstatte contains one of the world's most diverse fish assemblages. It includes over 65 species of remarkably well-preserved sharks (Lund & Grogan 2005). Some specimens even have skin pigments and internal organs preserved (Grogan & Lund 1997).

During this Golden Age, sharks were at their highest diversity; there was a profuse amount of families, genera,

and species. They came in all shapes and sizes, from a few inches to over 20 feet. Some lived in freshwater,

while others lived in salt water. Some were beginning to look like modern sharks, while others took on unique,

highly specialized forms. Some examples include the large whorl tooth shark, Helicoprion, which had replacement

teeth arranged in spirals. The shark Belantsea Montana looked more like a fancy tropical aquarium fish than a

shark. The entire Stethacanthus genus had a large anvil shaped dorsal fin, unlike anything that exists today.

The Carboniferous was truly the Golden Age of Sharks.

This is the shark, Falcatus falcatus of the Lower Carboniferous, Montana, USA; State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe, Germany. Image credit: Von H. Zell - Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 3.0

This image shows the Carboniferous fossil shark tooth Glikmanius occidentalis (formerly called Cladodus).

The Glikmanius genera lasted into the Permian.

This specimen was found in the Ames Limestone near Pittsburgh, PA. It is Pennsylvanian in age and is approximately 300 million years old.

Glikmanius has a large central crown surrounded by a series of cusps on either side. The cusps are broken off on one side of this specimen.

This fossil shark tooth is 1.2 cm across, and would be about 1.5 cm if complete.

The Permian - The Near Extinction of Sharks - 298 Mya

This is a Permian Orthacanthus shark fossil from Germany on display at the Natural History Museum in Vienna. Image By: Tommy from Arad (Uploaded by FunkMonk) - [CC BY 2.0]via Wikimedia Commons

During the next time period, the Permian (starting around 298 million years ago), some of the more specialized shark genera became extinct. Sharks were still diverse, just not as diverse as in the Carboniferous. However, this all came to an abrupt end at the end of the Permian. The end of the Permian is marked by "The Big One," Earths largest mass extinction EVER!

This extinction was so large, that it is used to mark the end of the entire Paleozoic Era.

Life on Earth looked fundamentally different after this extinction. The common animals that

existed for hundreds of millions of years vanished. After the Paleozoic Era, there are no trilobites, eurypterids,

horn corals, graptolites, or spiny sharks (a cross between a shark and a bony fish). The list goes on and on. Any surviving

life was severely reduced as 80 - 95% of all species became extinct (Benton et al 2004). Causes of this extinction are

linked to an abrupt climate change. The specific causes are still being debated. Whether it was the formation of Pangaea,

extreme volcanism, other geologic activities, an asteroid(s), or any combination thereof does not change the fact that

almost all life on Earth was wiped out. Life barely squeaked by this one. Sharks barely survived this extinction event.

One of the better known sharks from the Permian is Orthachanthus, a large freshwater eel-like shark.

A complete specimen from Germany is shown above.

Mesozoic - Modern Beginnings - 252 Mya

The first period in the Mesozoic Era, the Triassic (252 Mya), is an interesting time period as life on Earth began a slow recovery from the Permian mass extinction.

The few surviving taxa, both on land and sea, radiated and diversified creating new ecosystems. Although mammals make their appearance,

reptiles were the main creatures to dominate these new ecosystems.

They dominated the land, via dinosaurs. They dominated the air, via flying reptiles. They also dominated the seas with a new terrifying kind of animal,

the Great marine reptiles. These sea monsters were fierce predators that ruled the Mesozoic oceans. The surviving sharks took a back seat to these terrifying beasts.

Although sharks took a back seat to the Great marine reptiles, they continued to diversify

and took on their modern looking characteristics. By the end of the the Jurassic period in the Mesozoic,

all eight extant shark orders appeared. At the close of the Mesozoic era, at the end of the Cretaceous period 66 mya, a great mass extinction event

took out most of the reptiles. The Dinosaurs, flying reptiles, and great marine reptiles all disappeared. This allowed

sharks to, once again, become the top predators.

The teeth in this image include: Scapanorhynchus texanus (Extinct Goblin Shark), Squalicorax pristodontus (Extinct Crow Shark), Ptychodus sp. (Extinct Shell-Crushing Shark), and Cretolamna appendiculata (Extinct Mackerel Shark).

All were found near Big Brook, NJ, except for the Ptychodus, it was found in Sherman, TX.

The largest tooth measures 4.5 cm in height.

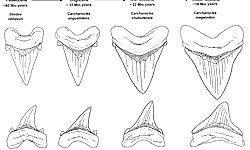

Cenozoic - The Rise of Giant Sharks - 65 Mya

Sharks grew into giants in the Cenozoic. The Megalodon shark is a prime example. This is a Megalodon shark model at the Calvert Marine Museum in Maryland.

During the new era, the Cenozoic, a new food source appeared. Mammals returned to the ocean (whales, dolphins, seals, etc...).

This proved to be a new and easy food source for sharks. As a result, the modern looking sharks grew. This period saw

the birth of the world's largest and most fearsome shark, the Megatooth shark. This beast originated in the Paleocene

with the Otodus genera, and slowly became larger and larger through time until the apex species emerged in the Miocene (23 Mya), Carcharocles Megalodon. Think of this giant Megatooth shark as a 60-foot Great White! Other sharks during this time period

also became super sized. A good example is the Giant White sharks (Cosmopolitodus). These are non-serrated, larger

versions of the Great Whites. Luckily, for humans, the large sharks became extinct at the end pliocene extinction event around 2.5 Million years ago.

To learn more about the megalodon shark,

click here to go to the megalodon

gallery page

This is a sample of the giant fossil sharks of the pliocene. Fossil shark teeth include Carcharocles megalodon (Extinct Megatoothed Shark), Carcharodon carcharias (Great White Shark), and Cosmopolitodus xiphodon (Extinct Giant White Shark).

The lower left tooth was found at the Calvert Cliffs of MD, The lower right tooth was found by Black water diving in SC., and the rest were found in the PCS Phosphate mine in Aurora, NC.

The largest tooth measures 15.2 cm.

Conclusion:

The fragmentary fossil record shows that sharks originated sometime in the Ordovician. The fossil record also shows sharks have continually evolved and changed. Many shark designs, from freshwater forms, to sharks with bizarre shapes, and even giants, have come and gone. These adaptations have allowed sharks to survive every mass extinction event and thrive to the present day.

One remarkable thing about nature is that we can go out and find these prehistoric remains. To find your own prehistoric shark fossils,

click here to go to the fossil hunting location page for more information.

Recommended Shark Books

Get Your Very Own Megalodon Tooth:

These are Authentic Megalodon teeth sold by Fossil Era , a reputable fossil dealer (that I personally know) who turned his fossil passion into a business. His Megalodon teeth come in all sizes and prices, from small and inexpensive to large muesum quality teeth. Each tooth has a detailed descriptions and images that include its collecting location and formation. If you are looking for a megalodon tooth, browse through these selections!

References / Works Cited

Andreev, P., Coates, M. I., Karatajute-Talimaa, V., Shelton, R. M., Cooper, P. R., Wang, N.-Z., & Sansom, I. J. (2016). The systematics of the Mongolepidida (Chondrichthyes) and the Ordovician origins of the clade. PeerJ, 4, e1850. http://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1850

Benton M.J., Tverdokhlebov V.P., Surkov M.V. (2004). Ecosystem remodelling among vertebrates at the Permian-Triassic boundary in Russia: Nature, v. 432: 97-100.

Grogan, E.D. & Lund, R. (1997). Soft tissue pigments of the Upper Mississippian chondrenchelyid, Harpagofututor volsellorhinus (Chondrichthyes, Holocephali) from the Bear Gulch Limestone, Montana, USA. Journal of Paleontology, v. 71: 337-342.

Hansen, M. C., (1996). "Phylum Chordata-Vertebrate Fossils," in Fossils of Ohio, edited by R. M. Feldmann and Merrianne Hackathorn. Ohio Division of Geological Survey Bulletin 70, pp. 288-369.

Karatajute-Talimaa VN, Novitskaya L, Rozman KS, Sodov Z. (1990). Mongolepis-a new lower Silurian genus of elasmobranchs from Mongolia. Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal. 1990;1:76-86.

Lund, Richard & Grogan Eileen. (2005). "Fossil Fishes of Bear Gulch." Saint Joseph's University. March 20, 2012. (http://www.sju.edu/research/bear_gulch/index.php).

Maisey, J. G., Miller, R., Pradel, A., Denton, J. S.S., Bronson A., & Janvier, P. (2017) Pectoral Morphology in Doliodus: Bridging the 'Acanthodian'-Chondrichthyan Divide, American Museum Novitates Number 3875 :1-15. 2017

https://doi.org/10.1206/3875.1

Miller, R. F., R. Cloutier, and S. Turner. (2003). The oldest articulated chondrichthyan from the Early Devonian period. Nature, v. 425: 501-504.

Qu, Qingming & Zhu, Min & Zhao, Wenjin. (2010). Silurian atmospheric O2 changes and the early radiation of gnathostomes. Palaeoworld. 19. 146-159.

Sansom, I.J. & Davies, N.S. & Coates, M.I. & Nicoll, R.S. & Ritchie, A. (2012). Chondrichthyan-like scales from the middle Ordovician of Australia. Pelaontology, 55 (2): 243-247.

Sansom I.J, Smith M.M, Smith M.P. (1996). Scales of thelodont and shark-like fishes from the Ordovician of Colorado. Nature, v. 379: 628-630.

Tajute-Talimaa V. (1973). Elegestolepis grossi gen. et sp. nov., ein neuer Typ der Placoidschuppe aus dem Oberen Silur der Tuwa, Palaeontographica, A. 143: 35-50.

Zerina Johanson, Mikiko Tanaka, Natalie Chaplin, and Moya Smith. (2008). Early Palaeozoic dentine and patterned scales in the embryonic catshark tail. Biol Lett 4: 87-90.