Article written by: Jayson Kowinsky - Fossilguy.com

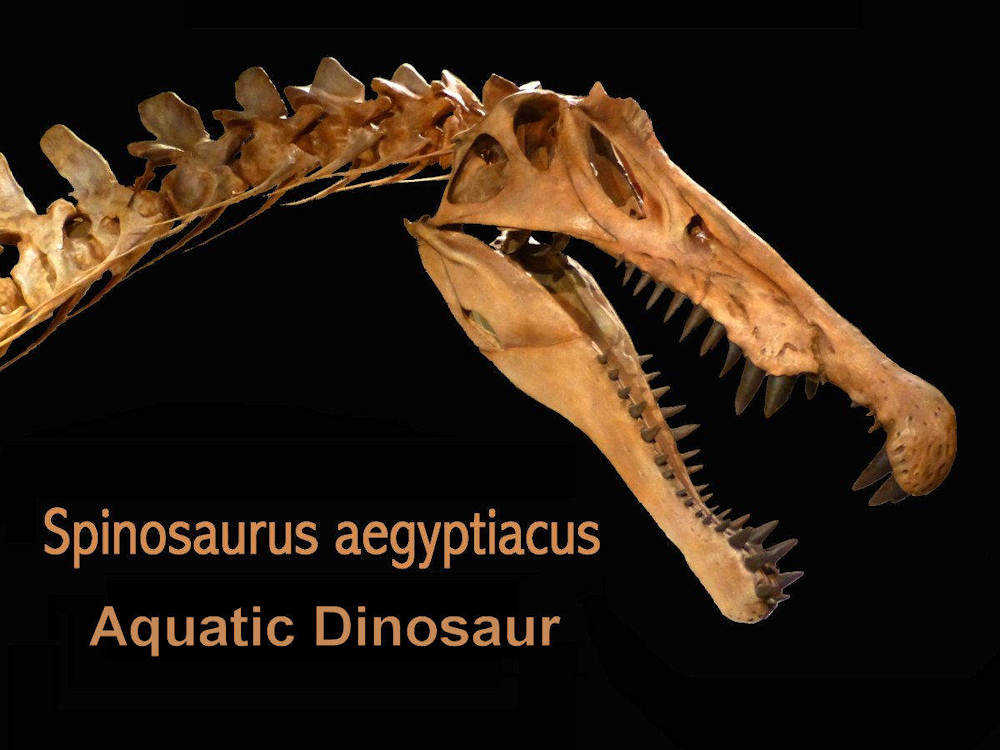

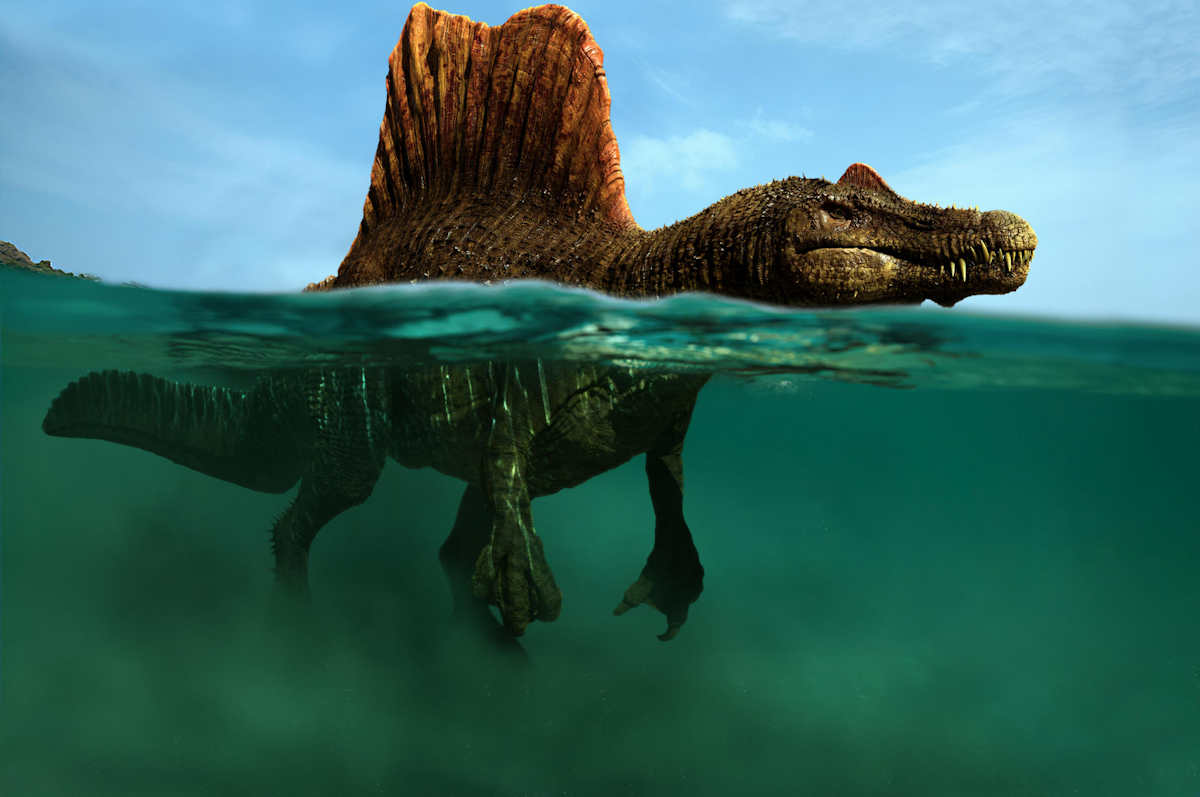

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus wading in shallow water, possibly stalking fish. Rendering by Julian Johnson-Mortimer (CC BY 3.0).

Spinosaurus Dinoasur showing the Aquatic/Swimming Posture

Fast Facts about Spinosaurus

Image from a Sketchfab model by Julian Johnson-Mortimer of Spinosaurus based on the new research. This updated Spinosaurus model has a long and clearly paddle-like tail designed for water propulsion.

Name:

Spinosaurus aegypaticus (pronunciation: "SPINE-oh-SAW-rus") - The name means "Spine lizard of Egypt"

Taxonomy:

Dinosauria (Dinosaur) - Saurischia (Lizard Hipped) - Theropoda (Beast Footed) - Spinosauroidea aka Megalosauroidea (Superfamily) -

Spinosauroidea (Family) - Spinosaurus (Genus) - S. aegyptiacus (species)

Age: Mid Cretaceous

Spinosaurus lived during the Cenomanian and Albain ages 94-110 million years ago.

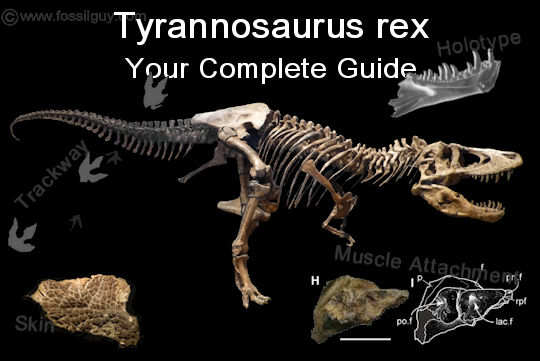

Spinosaurus became extinct 30 million years before T-rex appeared.

Discovery: Stromer, 1915

In 1912, Richard Markgraf found a partial specimen in the Baharia Oasis of Egypt. He sent the fossils to Ernst Stromer in Germany for study, and in 1915 this dinosaur was named Spinosaurus.

Distribution: North Africa:

Other Spinosaurid dinosaurs have been found globally, from Brazil, Asia, Europe, to Australia, but S. aegyptiacus is only found in Northern Africa.

Fossil locations include Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Lybia, and even Kenya.

Body Size: The Biggest! 15 meters (49 feet)!

With a skull of over 4 feet in length, Spinosaurus a. wins the record as the longest theropod.

It was a full 10 feet longer than T. rex, and about 7 feet longer than Carcharodontosaurus, a T. rex like theropod that lived alongside Spinosaurus.

However, Spinosaurus had a very long tail and a long neck, so Carcharodontosaurus and T. rex would have been bulkier!

Diet: Fish

Spinosaurs teeth and jaws were designed for eating fish.

Designed For the Water: Unlike other theropods, this dinosaur is very specialized.

Some of the specializations discussed in Ibrahim's papers (2014 and 2020) include:

* A crocodile like head with a long, slender snout that had many interlocking pointy teeth for grasping large fish

* Pressure sensors in the snout to detect moving prey in the water, just like crocodiles

* A long, crocodile like tail that was ideal for propulsion in water

* Possible webbed back feet

* Hind legs that were better at a paddling motion (for swimming) than a walking motion

* Front arms that were very robust with rigid hands; probably to support its weight when walking, since it had to walk on all four legs

* Nostrils that were positioned further up on the skull, enabling it to breathe while mostly submerged

* A dense bone structure, just like cetaceans (whales) and other aquatic mammals, for better buoyancy for swimming and diving

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus fossils have been found in the following formations:

| Mid-Late Cretaceous Formations | Locations |

|---|---|

| Bahariya Formation | Egypt |

| Aoufous Formation (Kem Kem Beds) | Morocco |

| Tegana Formation (Kem Kem Beds) | Morocco |

| Chenini Formation | Tunisia |

| Cabao Formation | Libya |

| Turkana Grits Formation | Kenya |

| "Gara Samani" | Algeria |

| www.fossilguy.com |

A reconstructed Spinosaurus that was on display at the National Geographic Musuem in Washington D.C. This is the new, corrected mount, showing its aquatic posture, as it could not have walked on two legs.

Discovery / Paleontological History of Spionosaurus

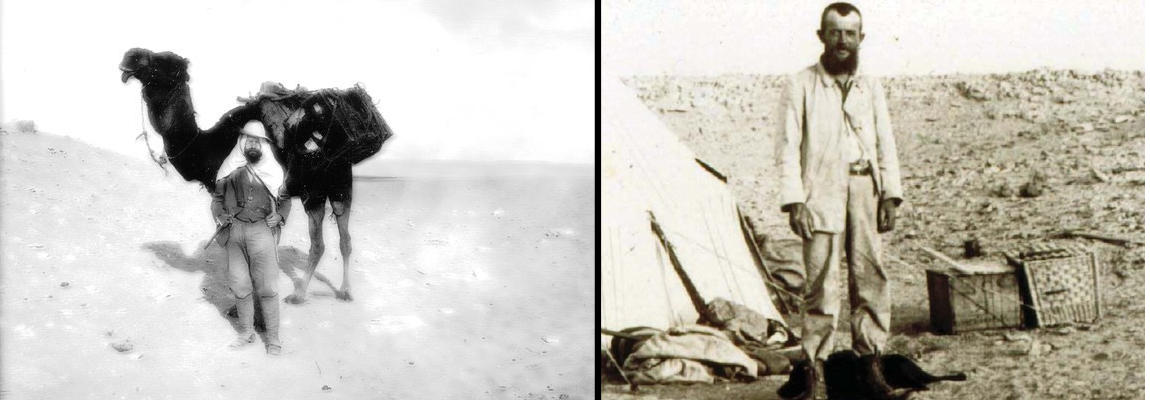

LEFT: Ernst Stromer on the expedition in Egypt in either 1911 or 1912.

RIGHT: Richard Markgraf on an earlier expedition with Osborn of the AMNH in 1907.

1911: Stromer and Markgraf: The Spine Lizard of Egypt

The story begins in 1911, when Ernst Stromer, a Bavarian paleontologist, launched an expedition to collect mammal fossils in the

little explored deserts of Egypt. Stromer met up with guide Richard Markgraf, an Austrian fossil collector who lived near Cairo.

For the most part, the expedition was a bust for mammal fossils; however,

in the Baharia Oasis of Egypt, Stromer discovered large creatacous dinosaurs, including several carnivores.

By 1912, Stromer returned to Germany and had Markgraf stay to continue excavations. In late 1912, Markgraf came across a partial

skeleton of a large and bizarre shaped dinosaur (Smith, et al. 2006). He shipped the material back to Stromer for study and in 1915

Stromer published a paper describing the specimen which he coined Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, the "Spine Lizard of Egypt."

1936: The First Reconstruction

Spinosaurus Fossil Illustrations from Stromers first spinosaurus publication in 1915. This is plate 2 from his publication.

More and more fragmentary fossils of Spinosaurus were discovered and sent to Stromer. By 1936 Stromer had enough material to make a reconstruction which showed it to be a huge, lumbering, bipedal carnivore with a giant sail on its back.

1944: The Complete Destruction

The Author looking at casts of Stromers original Spinosaurus fossils. These were on display at the National Geographic Museum.

Stomers Spinosaurus material had been on display at the Bavarian State Collection in Munich. When WWII began, Stromer tried desperately (but unsuccessfully)

to get his specimens moved out of Munich and away from Allied bombings. Unfortunately, in 1944, an Allied bombing run obliterated the museum and all of

Stromer's fossils.

This dinosaur was lost for years. Fragments of this dinosaur and its relatives would be found from time to time. However, nothing

substantial enough had been found to do an accurate analysis and reconstruction. Thus, Spinosaurus remained enigmatic for over 50 years.

2008 - 2020: Nizar Ibrahim - The New Specimens

In 2008, Ibrahim was doing fieldwork in the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds near Erfoud, Morocco. While there, he bought a small box that contained unusual

dinosaur bones. They were in an odd purple colored matrix with yellow streaks. The fossil also had an unusual looking cross-section.

When at the Natural History Museum in Milan, Italy a year later, Ibrahim was shown a partial dinosaur specimen from Morocco. He immediately

realized it was a very rare partial Spinosaurus and that the specimen looked identical to his small unusual fossils

with the purple/yellow matrix he purchased in 2008. Realizing that it might be the same specimen, he thought he may be able to find the exact

location and excavate more of it.

Ibrahim returned to Erfoud four years later to track down the fossil dealer. With many false leads he was about to give up. On his last day in Morocco, Ibrahim was sitting at a cafe and miraculously recognized the fossil dealer as he happened to walk by. The dealer brought Ibrahim to the dig site,

showing where the Spinosaurus was unearthed. Ibrahim, with the help of Paul Sereno (an expert on Spinosaurus), returned to the dig site with a

team and uncovered more of the specimen. Ibrahim and Sereno then took digital measurements of their new specimen, measurements

from Stromer's pictures, and digital measurements of other fragmentary finds in North Africa. They did an in depth analysis of all these fossils

and in 2014 pubished the most accurate reconstruction of Spinosaurus to date, a semi-aquatic dinosaur.

After Ibrahim's paper was published, he returned to Morocco and excavated an area next to his original specimen and in 2018 Ibrahim and his team uncovered

an 80% complete tail of a juvenile Spinosaurus. Since the tail is almost entirely absent in the previous specimen, this was the first time paleontologists

got a good look at a Spinosaurus tail. What they found was remarkable. The paddle shaped tail was ideally designed for propulsion in water. This confirmed that Spinosaurus swam and was aquatic in nature. Ibrihim and his team published these new findings in a 2020 paper. These aquatic adaptations are discussed below.

Aquatic Adaptations of Spinosaurus: Designed for Water

Members of the Spinosauroid family had some aquatic adaptations, but it appears Spinosaurus took those adaptations much further. Changes in the skull, legs, feet, neck, tail, and even the bone density made Spinosaurus look more like a crocodile or an early cetacean (whale) than a theropod dinosaur. Below are details on the aquatic adaptations:

YOUTUBE VIDEO - Spinosaurus Aquatic Adaptations

5 minute Video about Spinosaurus from Nature with Nizar Ibrahim's new findings from his 2020 paper.

The Teeth: Ideal for Grasping onto Fish

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus teeth are odd for

a theropod. Even Stromer realized they were unlike any other theropod's teeth. Instead of teeth with the typical serrated knife-like blade,

Spinosaurus teeth were long, round, and pointy, more like crocodile or odontocete (toothed whale) teeth.

Since the teeth are not blade like with serrations, they would do a horrible job at slicing and cutting through flesh

and bone. However, the peg-like teeth, like those of crocodiles, toothed whales, and even the sand-tiger shark, are ideal

for grasping and holding onto fish.

This image shows a peg-like Spinosaurus tooth and a similar sized Carcharodontosaurus tooth (T. rex of Africa). Notice the tooth designs are completely different. The Spinosaurus tooth is ideally suited for grasping, while the Carcharodontosaurus tooth is idealy suited for slicing and cutting.

The Skull: Like a Crocodile

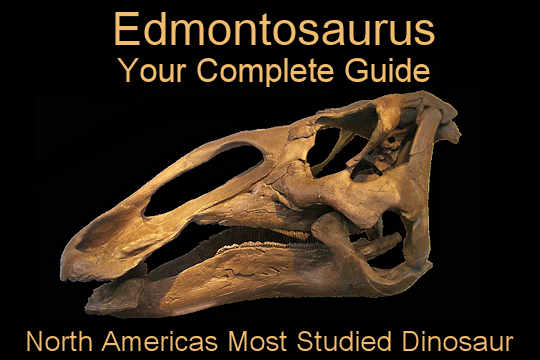

Like the teeth, the jaws of Spinosaurus are suited for capturing fish. They are very similar to the narrow jaws of the Gavial, a type of fish eating crocodile. These narrow jaws are clearly much weaker than other large theropods such as T. rex and Carcharodontosaurus. They lack the huge muscle

attachment areas. This means they are not suitable for clamping onto large struggling prey and tearing chunks of flesh from them. Just like the Gavail,

they are more suitable for grasping onto smaller prey, like fish.

The front of the snout contains has an array of small openings. In the 2014 publication, Ibrahim, et al. states these are very similar to the foramina

in crocodiles. These foramina contain pressure receptors that can detect moving prey under water.

One difference between Spinosaurus skulls and crocodile skulls is the nasal openings. Ibrahim also states that the nostril of Spinosaurus is positioned

toward the posterior end of the skull. This would help keep water out, and allow Spinosaurus to better breathe when mostly submerged. A similar

design can be seen on early cetaceans (whales).

This image shows a comparison between an American Alligator skull and a Spinosaurus skull. Notice the striking similarities. American Alligators mainly eat fish. Image of the American Alligator by: By Didier Descouens (Own work). CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The Limbs and Tail: Made for Swimming

The Tail: Designed for water propulsion

The tail is unique in Spinosaurus. It's unusually long, has very tall processes, and is unusually flexible.

Other theropods have very rigid tails that are used as a counterbalance. Spinosaurus tail is paddle shaped

designed to bend laterally (Ibrahim, et al. 2020). This is the same design that is seen in bony

fish and crocodiles. This means Spinosaurus' tail was probably used for propulsion when swimming and diving.

The Hind Limb: Designed for swimming, not walking

Ibrahim discovered the pelvis was reduced and the hind limbs, such as the femur, were short. However, these shortened hind limbs have robust

muscle attachments (Ibrahim, et al. 2014). Ibrahim notes this same type of design is found in early cetaceans (whales), and semiaquatic

mammals that use their hind limbs for paddling in water. Spinosaurus' hind legs were better designed for swimming than walking.

Ibrahim also noticed huge differences in the hind feet when compared to other large theropods. The hind feet are flattened and resemble

the feet of shorebirds, Ibrahim suggests the hind feet were adapted for walking on soft substrates, or were even webbed for paddling in water (Ibrahim, et al. 2014).

Another unique finding is that Spinosaurus' center of gravity is shifted toward the rib cage, whereas all other theropods the center of

gravity is over the hips. This means it would have been very difficult to walk on its short back legs. All other theropods are bipedal.

Ibrahim suggests Spinosaurus was not bipedal, but needed its forelimbs to walk (Ibrahim, et al. 2014 and 2020).

Image of the Spinosaurus tail excavated in 2018. It is designed for water propulsion. This is from the extended data - Fig. 4 from Ibrahim et al. 2020. Scale Bar is 1 m.

Bones like an Early Cetacean (Whale)

Another interesting finding from Ibrahim's paper is the bone density of Spinosaurus. Some of the bones samples had a bone

density 30-40% greater than that of other theropods, including other early spinosaurids (Ibriham, et al. 2014).

A high bone density is found in aquatic and semi-aquatic mammals. It helps with buoyancy when diving and swimming.

A similar bone density is also found in early cetaceans (whales). Their bone density increased as they were adapting

to the water. Clearly, Spinosaurus was adapting to life in an aquatic environment.

This is Maiacetus, an early cetacean (whale). Its bone density is much higher than land mammals.

This cast is on display at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

The Sail of Spinosaurus

Spinosaurus has HUGE processes on its dorsal vertebra. They can reach lengths of over 5 feet! They are the tallest processes on any dinosaur.

Stromer believed these processes formed a large sail on its back, like some reptiles. However, there was never enough fossil evidence to

determine what these large processes were actually for. Later, some people proposed they formed a large hump on its back. Others thought

it was for heat regulation.

Fortunately, a partial specimen in the 2014 paper has some well preserved dorsal processes. These spines are very dense and are not

vascularized; this means it would not have served as a heat regulatory function. They also found the edges of the spines to have

ligament scars. This means it would not have been a hump, like on a buffalo, but instead wrapped tightly in skin (Ibrahim, et al. 2014).

They therefore conclude the large spines would have functioned as a sail on the dinosaur's back, possibly serving as

a display structure that would have been visible while swimming (Ibrahim, et al, 2014). So, Stromers original

idea was correct; it was probably a large sail.

Conclusion and 3D model

The remarkable rediscovery of this intriguing dinosaur gives scientists enough information to clearly say Spinosaurus was at least semiaquatic.

Spinosaurus was a theropod that was not bipedal, as it had the wrong center of gravity and short stubby hind legs.

It had a crocodile-like skull and teeth for grasping onto fish, with crocodile-like water pressure sensors.

It had nasal openings set away from the front of the snout with dense bones, just like early cetaceans.

It had a long flexible Mosasaur-like tail, and wide flat feet like shorebirds.

Spinosaurus was truly an evolutionary masterpiece, designed for the water.

However, some paleontologists disagree with Ibrahim's research. In 2018, Henderson simulated Spinosaurus' buoyancy using it's bone

density and lung placement. He determined it could not dive and was unstable at the surface, as the sail would cause it to

roll to one side. Another paper by Hone and Holtz in 2021 also suggests Spinosaurus was not fully aquatic, but instead stayed along the waters edge stalking fish.

It looks like more research is necessary to make a final conclusion about Spinosaurus.

Below is an interactive 3D model of Spinosaurus that uses the new findings including the paddle-like tail that is clearly designed for water propulsion.

3D INTERACTIVE MODEL - Spinosaurus with Texture - Tap to Start Model

Interactive 3D Model of Spinosaurus by Julian Johnson-Mortimer (CC BY 4.0) on Sketchfab

Recommended Dinosaur Books and Educational Items:

Get Your Very Own Spinosaurus Tooth:

These are Authentic Spinosaurus teeth sold by Fossil Era Although Spinosaurus bones are rare, Spinosaurus teeth, like the one pictured here, are fairly common, because, like all dinosaurs, they shed their teeth regularly. They are great gifts for the fossil fanatic! Who knew you could own a real tooth from one of the largest theropods to exist! The teeth that Fossil Era sell come in many different sizes and prices, from small to large and museum quality. Check them out, they make great gifts!

Allain, R.; Xaisanavong, T.; Richir, P.; Khentavong, B. (2012).

"The first definitive Asian spinosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the early cretaceous of Laos".Naturwissenschaften 99 (5): 369-377. 99 (5)

Barrett, P.M., Benson, R.B.J, Rich, T.H., and Vickers-Rich, P. (2011).

"First spinosaurid dinosaur from Australia and the cosmopolitanism of Cretaceous dinosaur faunas."

Biology Letters online preprint: doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0466

Buffetaut, E. and M. Ouaja. (2002). "A new specimen of Spinosaurus (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Lower Cretaceous of Tunisia

, with remarks on the evolutionary history of the Spinosauridae." Bulletin de la Societe Geologique de France 173/5:415-421.

PDF file

Henderson DM. (2018). A buoyancy, balance and stability challenge to the hypothesis of a semi-aquatic

Spinosaurus Stromer, 1915 (Dinosauria: Theropoda) PeerJ 6:e5409 DOI: 10.7717/peerj.5409

Ibrahim, N., Maganuco, S., Dal Sasso, C. et al. (2020). Tail-propelled aquatic locomotion in a theropod dinosaur. Nature.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2190-3

Ibrahim, N., Sereno, P. C., Dal Sasso, C., Maganuco, S., Fabbri, M., Martill, D. M., Zouhri, S., Myhrvold, N., Iurino, D. A. (2014).

"Semiaquatic adaptations in a giant predatory dinosaur". Science.

Kellner, A.; Azevedo, S.; Machado, A.; De Carvalho, L.; Henriques, D. (2011). "A new dinosaur (Theropoda, Spinosauridae)

from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) Alcantara Formation, Cajual Island, Brazil" Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias, 83 (1), 99-108

PDF file

Martill, D. M., Cruickshank, A. R. I., Frey, E., Small, P. G., Clarke, M. (1996).

"A new crested maniraptoran dinosaur from the Santana Formation (Lower Cretaceous) of Brazil". Journal of the Geological Society 153: 5.

doi:10.1144/gsjgs.153.1.0005.

Sereno, Paul C., Beck, Allison L., Dutheil, Didier B.

Boubacar Gado, Hans C. E. Larsson, Gabrielle H. Lyon,

Jonathan D. Marcot, Oliver W. M. Rauhut, Rudyard W. Sadleir,

Christian A. Sidor, David D. Varricchio, Gregory P. Wilson,

Jeffrey A. Wilson (1998). "A Long-Snouted Predatory Dinosaur from Africa and the Evolution of Spinosaurids" Science 282, 1298;

DOI: 10.1126/science.282.5392.1298

Joshua B. Smith, Matthew C. Lamanna, Helmut Mayr, and Kenneth J. Lacovara. (2006). "New Information Regarding the Holotype of

Spinosaurus Aegyptiacus Stromer, 1915" The Paleontological Society; J. Paleont., 80(2), 2006, pp. 400-406.

Taquet, P., and Russell, D.A. (1998). "New data on spinosaurid dinosaurs from the Early Cretaceous of the Sahara".

Comptes Rendus de l'Academie des Sciences - Series IIA - Earth & Planetary Sciences 327 (5): 347-353.

PDF file